Credibility and Relatability: Autobiography in the Past and Present

“An autobiography is a book a person writes about his own life and it is usually full of all sorts of boring details,” wrote Roald Dahl in Boy: Tales of Childhood, in which he, rather ironically, describes his childhood and the experiences that influenced him into becoming an author. Autobiographies and memoirs have been present in literature for centuries. While the terms “autobiography” and “memoir” are often used interchangeably, there is some difference between the two. Autobiographies tend to be a more comprehensive account of an individual’s life. Memoirs, meanwhile, often focus on specific events and often portray memory with more intimacy and emotion.

One of the earliest examples of autobiography is Saint Augustine’s Confessions, written in approximately 400 CE. The work centers on Christianity through a descriptive account of Augustine’s life and conversion to Christianity. Works written prior to Augustine, such as Caesar’s Commentaries, might be considered predecessors of sorts – Caesar’s work gives more focus to the conquest of Gaul and less to the man behind it. These examples, while considered autobiographies, adhere more closely to the modern definition of a memoir. The modern autobiography, on the other hand, is considered to have come about during the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance, through The Book of Margery Kempe, the first English language autobiography, and, later, Pope Pius II’s account of his life and career over eleven books.

One of the greatest traps of autobiographies and memoirs is the credibility of the author. One could argue that the person who witnessed all of the events being described – the author themselves – is the best source of information about them, but memory and subsequent description can be faulty. In the case of biography, authors are required to do extensive research; the absence of credible sources would be an immediate red flag to readers. Autobiographies, however, are more difficult. Perhaps errors can be found if the writer describes well-known events incorrectly, but many personal details are sometimes hard to confirm beyond what the writer asserts. Additionally, while no work can be entirely free of bias, autobiographies and memoirs often involve subjective experience that can sometimes be misleadingly presented as fact.

French philosopher Louis Marin wrote of Jean Racine, the historiographer employed by King Louis XIV, as an example of the difficulty of providing an accurate and objective history. Racine’s job was to document Louis XIV’s travels, but the implicit requirement that he only write what the king approved of made it more of an autobiography via a scribe. Whatever Louis XIV wanted altered about the story would be dutifully changed, even if both he and Jean Racine experienced events differently. Presumably, Louis XIV was concerned with how he as a monarch would be remembered, and that bias now makes readers question the truth in descriptions of adoring villages and townspeople that he visited. What ends up being omitted actually sets up what Marin describes as a “trap of narrative” – what Racine and, by extension, the king, choose to remove actually draws more attention to itself in its absence. What is missing, and why is it missing? What does not line up with other knowledge that we have, and why does it not?

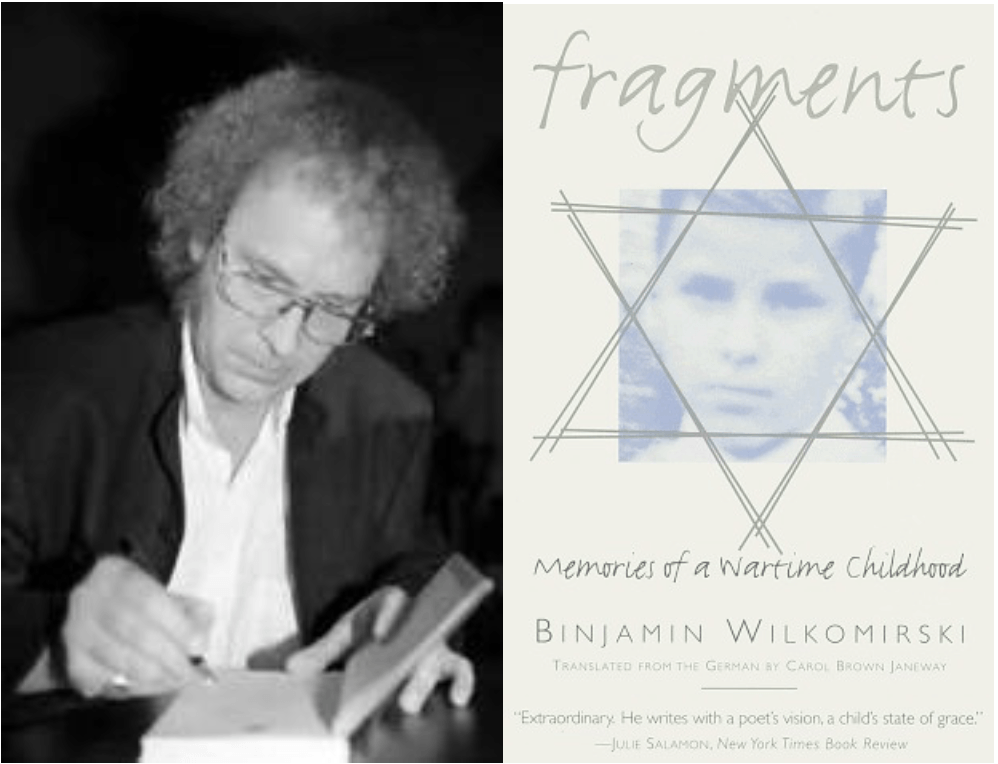

In the modern day, these questions are still important when reading autobiographies and works whose authors claim to be the authority on events. In 1995, Binjamin Wilkomirski published a harrowing account of his survival of the Holocaust as a child. Wilkomirski recounts the horrors he had seen in death camps in Poland, and his experience with an adoptive family that tried to reconstruct his memories after liberation. Wilkomirski’s book was praised as a masterpiece for its child’s-eye perspective, given awards, and quickly translated into multiple languages.

Then, a journalist named Daniel Ganzfried did some research into Wilkomirski’s past, having previously written a record of his own father’s experience in Auschwitz. He found that among many other fabrications, Wilkomirski was not Jewish and had never been held in a concentration camp. In the aftermath of the revelation, Wilkomirski refused to acknowledge the book as a fiction, apparently truly believing the story he told despite wide-ranging evidence to the contrary. This in turn raised concerns about his mental health. Other widely publicized cases of fictitious memoirs include James Frey’s A Million Little Pieces, in which his story of addiction and rehabilitation was found to have been highly exaggerated. Frey, however, has publicly admitted to the fabrications, and continued on with a career as a writer.

Binjamin Wilkomirski (born Bruno Grosjean, and later Bruno Dössekke, alongside the cover of his book. Source: Goodreads

Autobiographies have branched out as publishing becomes more accessible to the average person. Celebrity memoirs continue to line shelves with notable recent ones from Julie Andrews and Michelle Obama. The trend, however, seems to be that people are searching for personal content from more relatable sources, with autobiographies from “everyday folk in everyday jobs” (as a May article from the Guardian describes them) becoming more popular. An example is Christie Watson’s The Language of Kindness: A Nurse’s Story, in which she delivers haunting and poignant stories, taken from twenty years of experience working in hospitals.

The same Guardian article mentions that perhaps Watson’s stories are much more likely to ring true in the lives of the average reader than the “kiss-and-tell memoirs of a celebrity sitting on a yacht in St Tropez.” The rise of social media may also have led to this shift. There is no longer a need to read a book to learn intimate details of a celebrity’s life. This is not entirely true, given the controversy and buzz around figures like Demi Moore, whose recent book made tabloid headlines after she laid out claims of her ex-husband, Ashton Kutcher’s infidelity, and Lena Dunham, who was accused of sexually abusing her younger sister after the publication of her memoir Not That Kind of Girl: A Young Woman Tells You What She’s “Learned.”

Lena Dunham and her memoir, pictured in the New York Times in 2014.

Whether from actresses or hospital nurses, there has always been an audience for personal expression and anecdotes, and the platform for them has become increasingly accessible in recent years. At their worst, autobiographies can turn out to be exaggerations or fabrications for the sake of a good story; at their best, they can be poignant and provide insight into another person’s rich life experience.

At their worst, autobiographies can turn out to be exaggerations or fabrications for the sake of a good story; at their best, they can be poignant and provide insight into another person’s rich life experience.