The Dead Sea Scrolls: Ancient Texts and Modern Forgery

Allison Zhao, Author

For two thousand years, the Dead Sea Scrolls lay hidden. They were discovered in 1947 in the West Bank and became incredibly important artifacts for archaeologists and scholars as some of the oldest biblical texts ever discovered. Over the next several decades the various Scrolls were sold and scattered between various collectors and museums. One such museum, the Museum of the Bible in Washington, D.C., proudly displayed sixteen fragments of the Dead Sea Scrolls, until this past March, when National Geographic reported that a team of researchers had found that all of the museum’s fragments were fakes. This conclusion has important ramifications not only for the museum, but also for researchers studying the Scrolls, and for the history of Judaism and Christianity.

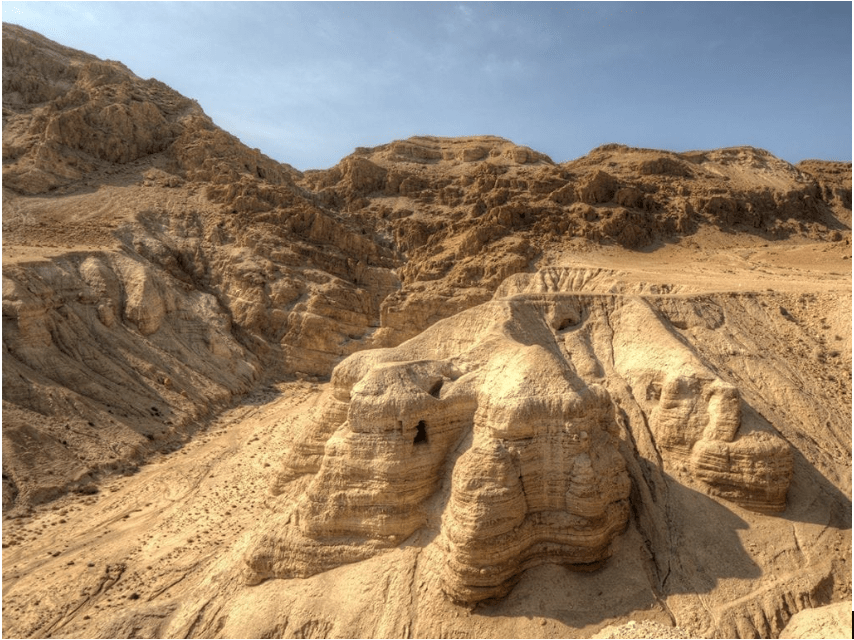

The Dead Sea Scrolls in general have been shrouded in mystery and are the subject of much debate. Excavation of the Qumran caves and further examination of the scrolls were delayed for four years after the Scrolls’ initial discovery due to the Arab-Israeli War in 1948. It is difficult still to even say who lived around the caves or who wrote the scrolls – there are many theories, but little definitive proof to point one way or another. Archaeologist Roland de Vaux, who led the original examination of the site, described Qumran as a former religious community. This theory was popular for a while, with some believing that Jewish ascetics known as Essenes inhabited the caves. It may have been home to a group of scribes, or perhaps priests who had broken off to form their own small society. Some believe that the scrolls were hidden in the caves as Jews fled the Romans after Galilee fell during the Jewish revolt. In ancient times, the area around Qumran was an active community, with Jerusalem, Jericho, and settlements around the Dead Sea all within a day’s travel. The site where the scrolls were found might have been anything from a manor house to a manufacturing center to a tannery, and may have transformed over time.

(Above) An image of the caves at Qumran, where the scrolls were discovered.

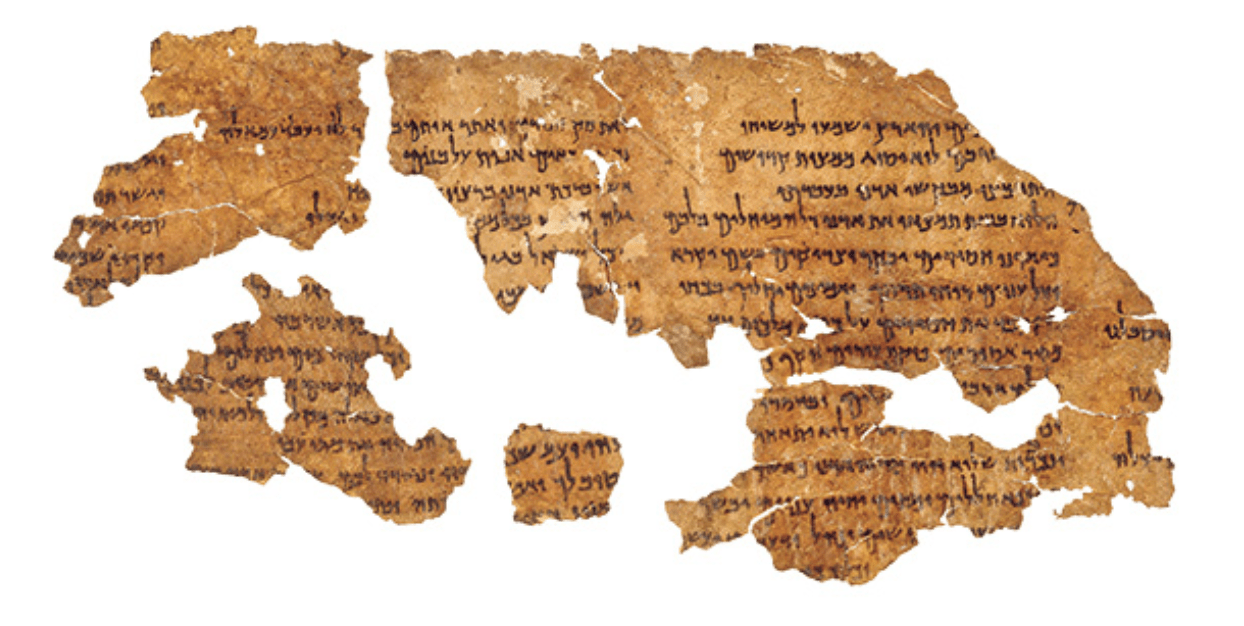

It is generally understood that the scrolls did not originate from Qumran, as they are written in multiple languages, including complex Greek, when an ascetic community living in Judaea would be expected to use Aramaic or Hebrew, and likely in simpler form. There are a few nearly intact scrolls, as well as thousands of fragments of various sizes. Texts from almost every book of the Hebrew canon (otherwise referred to as the Old Testament) can be found among them, with the notable exception of the Book of Esther. It is possible that the book was intentionally omitted because it was not part of the beliefs of the sect that created the Scrolls; however, it also may have disintegrated over time, or, perhaps it has simply not yet been discovered in the caves. The Scrolls include one of the earliest known versions of the Ten Commandments, as well as hymns and prayers that had previously been unknown. They date from around 200 BCE to the 1st century CE and provide insight into how the canon of the Hebrew Bible evolved over time. For example, there is a first-person narrative by Abraham of his travels in Chapter 13 of the Book of Genesis that no longer exists. Overall, though, the similarities to much more recent versions are extraordinary.

(Above) An example of a Dead Sea Scrolls fragment

In the present day, the Dead Sea Scrolls are on display in Jerusalem as well as in a travelling exhibit. Between 2009 and 2010, there was also a special exhibit at the ROM displaying fragments. Washington D.C.’s Museum of the Bible believed they also owned similar fragments until the recent report that they were all modern forgeries. This discovery does not impact researchers’ confidence in the authenticity of the some hundred thousand fragments in Israel, but does cast some doubt on the “post-2002” fragments, which were a collection of roughly seventy pieces that appeared in the antiquities market more recently. During the 1950s, the pieces had been collected and sold until UNESCO and Israeli law limited how these fragments could be traded. The post-2002 fragments’ origins are largely unknown – possibly looted and smuggled. The team investigating the authenticity of the Museum of the Bible’s fragments was led by Colette Loll, an art fraud investigator with a background in art history, international art crime, and analyzing forgeries. She in particular insisted that the report her team produced would be final and not be impacted by any interference from the Museum of the Bible, to which the museum agreed prior to the start of her work.

One of the most important factors in identifying the fragments as forgeries is the material that the writing was done on. Authentic pieces of the scrolls tend to be on tanned parchment or papyrus, while the Museum fragments were made from leather. The leather appeared to actually be ancient, perhaps remnants of sandals or shoes found in the desert. Analysis with a microscope showed that the text was painted onto the leather after it had already become ancient; the ink pooled in cracks and leaked over torn edges, and some writing looked as though it had been squeezed to fit within the edges of the pieces. Similarly, a crust had built up on the leather over time, and the ink was on top of it rather than beneath it, as would be expected if the leather had been painted when new. X-ray analysis also indicated that lime may have been used to remove hair from the leather, a practice which is thought to only have become popular after the scrolls were written. There is also notable effort to hide these anachronisms and make a more convincing imitation, including using an amber-coloured glue to mimic hardened gelatin that appears on ancient parchment, and dusting the fragments with minerals that might feasibly be found at Qumran.

The fragments were all forged in a similar way, indicating that they likely come from the same source, but investigators have little to work with in terms of tracing their movement through the antiquities market until their arrival at the Museum of the Bible. Harry Hargrave, the CEO of the Museum, said in response to the forgery report, “We’re victims—we’re victims of misrepresentation, we’re victims of fraud,” and affirmed that the Museum of the Bible was working to be as transparent as possible on this issue. Moving forward, there is now an established procedure for identifying forgeries among the other post-2002 fragments. The Museum of the Bible has expressed a commitment to further evaluation of the way the Museum obtained them, as well as other artifacts, in the hopes of preventing further forgeries from making their way into collections, and to ensure that they are acquired via legal means.

“We’re victims—we’re victims of misrepresentation, we’re victims of fraud.”