Racial Diversity in Literature — What it Means and Why We Need It

“What I wanted, needed really, was to become an integral and valued part of the mosaic that I saw around me,” wrote Walter Dean Myers in a 2014 opinion piece for the New York Times, titled Where Are the People of Color in Children’s Books? He explains that when living through extremely difficult points of his life (including coping with the murder of his uncle, grief, and alcohol abuse by family members),reading books became a retreat from the world. He noted that the world he saw around him was not reflected in his reading material: “As I discovered who I was, a black teenager in a white-dominated world, I saw that these characters, these lives, were not mine.”

Diversity in literature has been a major topic of discussion for years, and in the light of the Black Lives Matter movement and heightened political tensions in both the USA and Canada, it has only become more important. There is a continued push from authors and readers alike to see more representation, both in the world of publishing and in fiction itself. While often focused on racial representation, the concept of diversity extends much further than that – it encompasses gender, sexuality, ethnicity, religion, disability, social class, and other aspects of identity.

Studies in children’s literature over the last several decades have found that it is quite homogenous in featuring mostly white characters – a 1965 study learned that only 6.7% of children’s books published in the preceding three years had featured any Black characters. Meanwhile, in 2013, another study found that only about 10% of children’s books featured people of colour from any background. It is particularly important that children’s literature and young adult books include diverse characters in order to help youth develop healthy self-images, as well as understanding of their own identity and that of others. People of any age from marginalized groups may already feel isolated in their communities, and fiction that consistently adheres to specific identities, and that does not acknowledge others, only compounds that feeling.

Publishing has historically been a predominantly white, upper-class industry, and it continues to reinforce itself as such. A 2019 survey from Publishers Weekly had 84% of publication employees respond that they were white or Caucasian. Another study by children’s publisher Lee & Low found similarly high percentages, and importantly, that this was an unchanging trend, even with recent movements for diversity. Getting jobs in publishing often first requires experience in the form of unpaid or low-wage internships, and the combination of relatively low salaries and publishing houses tending to be situated in expensive cities means that involvement in the industry is much more accessible to people from wealthier socioeconomic backgrounds. According to publishing executives, as reported by Associated Press News, entry-level positions and children’s publishing are the most racially diverse spheres, while higher-level editorial jobs and adult publishing are noticeably dominated by white people.

Publishers have ostensibly put forth efforts to diversify their workforce, as the major “Big Five” (Hachette, HarperCollins, MacMillan, Penguin Random House, and Simon & Schuster) have created opportunities such as internships, outreach, and mentoring programs that are meant to open up the industry to people from diverse backgrounds. Imprints dedicated to promoting marginalized voices, such as One World (from Penguin Random House) and 37 Ink (Simon & Schuster), have also existed for years, but highly publicized missteps also demonstrate that the road to truly diverse publishing and fiction is not a smooth one.

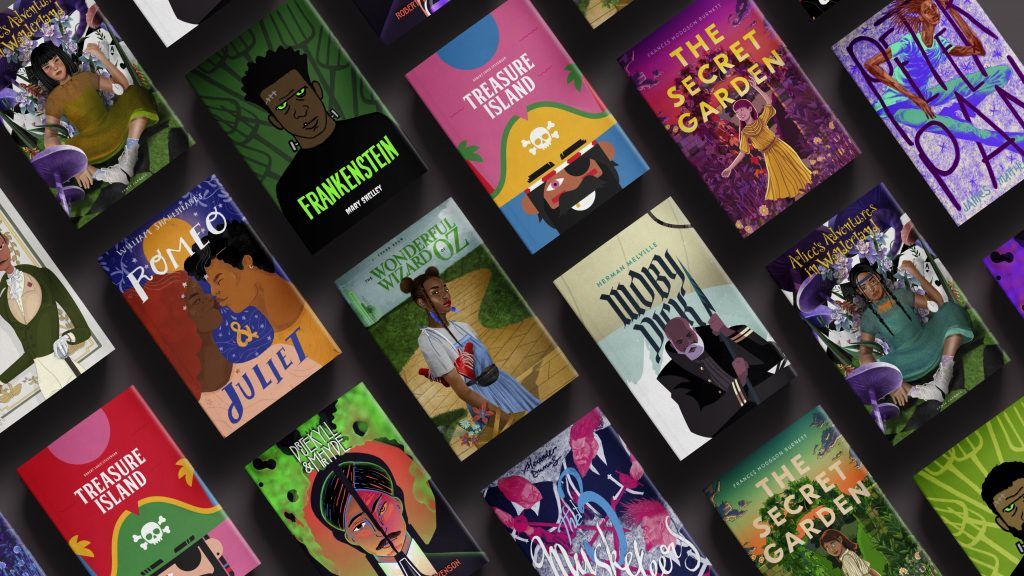

A recent example is the controversy surrounding Barnes and Noble’s “Diverse Editions,” in collaboration with Penguin Random House – a project seemingly intended to promote representation of different races and ethnic groups in literature. Twelve popular classic young adult works were receiving redesigned covers to portray people of colour, such as Frankenstein, The Secret Garden, Romeo and Juliet, and Emma, among others. An image posted to Publishers Weekly’s Twitter account shows some of the proposed covers, including Frankenstein’s monster being depicted with dark skin and Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde with a turban. According to the back cover of the books the premise was that “for the first time ever, all parents will be able to pick up a book and see themselves in a story.”

Reactions were swift, and strongly negative, with people pointing out that this movement did nothing to promote works by authors of colour or make the publishing landscape more accessible to them. Hugo-winning author Nnedi Okorafor, who is Nigerian-American, wrote that it was “fake diversity nonsense” and simply “disgusting.”

It could well be that Barnes and Noble truly wanted to make classic literature, which has historically been seen as overly focused on white narratives, into something more relatable to the children of colour who would grow up reading these stories. Where this project stumbles, beyond continuing to keep the spotlight on works by white authors instead of authors of colour, is that these books were selected for the initiative by artificial intelligence searching texts for explicit statements of characters’ ethnicities. This leaves a vital gap as to whether or not the stories contained cultural context for ethnicity – which most often, they do.

Mary Lennox, the protagonist of The Secret Garden, was born to British parents in colonial India and begins the story by going to England to live with her wealthy uncle on the Yorkshire Moors. There is a clear narrative context from which Mary’s ethnicity can be inferred, and as author Justina Ireland explained on Twitter, to depict Mary as a Black or brown-skinned child erases the real cultural differences of the time period. Instead, it creates the false idea that people of colour want to insert themselves into white narratives and continues to overlook the stories that they actually want to tell. Walter Dean Myers’s opinion piece in particular noted that the characters he was reading were not truly his, and that difference goes beyond simply whether or not the characters’ physically appearances are explicitly stated.

Another highly controversial debate regarding storytelling and representation came with the publication of American Dirt, a novel by Jeanine Cummins that tells of a Mexican woman who flees from cartel-related violence to the United States with her son. The novel was brought further into the spotlight when it was chosen for Oprah Winfrey’s book club, and heavily marketed as a ground-breaking story for Americans, especially relevant in the current political climate related to refugees and immigration. However, it was heavily criticized as being extremely unrealistic and exploitative, further complicated by the fact that Jeanine Cummins is a white woman with some Puerto Rican heritage, without any personal connection to the subject matter.

Esmeralda Bermudez, a writer for the Los Angeles Times and an immigrant who was directly impacted by violence in El Salvador, stated that “In 17 years of journalism…I’ve never come across anyone like American Dirt‘s main character” and “It’s painful that not only did I not see myself [in this book], but I found all these things that constantly make [Latinx people] feel small.” Similarly, Randy Boyogada, novelist and professor of English at the University of Toronto, wrote in The Atlantic that American Dirt was “fantasy fiction for suburban readers, with its plétora of italicized Spanish words… its damp lyricism, and its imperiled, resilient, working-mom hero.”

Ignacio M. Sánchez Prado, professor of Spanish and Latin American Studies at Washington University in St. Louis also had sharp criticism regarding Cummins’s “deep ignorance regarding Mexico and Mexicans in U.S. culture.” However, he welcomes non-Mexicans of all backgrounds learning and writing about Mexico with “authority and care,” which brings up the greatest lesson of the entire controversy: the vital difference that research makes, even in fiction.

Is there something inherently wrong with a white American writing about Mexican and Latinx people? Not necessarily; creative exploration does not have to be limited to the author’s own identity. The reason that many choose to tell stories related to aspects of their self (whether gender, race, sexuality, or beyond) is that they have authority on the experiences that they directly live. When expanding beyond the familiar, however, writers need to commit to doing their research to avoid playing into stereotypes, and this is where Cummins seems to fall short. Even her promotional events came under fire, when a photo was posted to Twitter of a dinner in celebration of the book: the floral centerpieces were wrapped in barbed wire in a recreation of the novel’s cover, which only highlighted how separate Cummins and her literary circle are from the reality of border tensions and refugees.

Centrepieces featured flowers and barbed wire at a dinner event for Cummins’s novel. Source: Myriam Chingona Gurba de Serrano (@lesbrains), Twitter

The demand for representation includes the desire for more stories about people of colour, and particularly the contemporary struggles they are subject to. A white author can contribute positively to this by providing a narrative that explores the experiences of marginalized groups with grace, or instead writing diverse characters into narratives that do not focus on discrimination or hardship for underrepresented groups – genres such as comedy, romance, and fantasy can feature all sorts of characters without having to dive deep into cultural history and politics. Even these avenues for representation, however, cannot replace the inclusion of writers of colour in the publishing industry. A novel that claims to represent a community – and, without a doubt, American Dirt does make this claim – but falls to stereotyping without nuance, instead does harm by reinforcing misconceptions. Cultural and lived experiences go much deeper than physical appearance and Western media portrayals, and incorporating them well into the literary landscape can only benefit huge numbers of readers who will better see themselves and their background in books.

Nnedi Okorafor perhaps sums up the situation best by saying, “New stories by people of color about people of color is the solution.” Diversity cannot be achieved with redesigned covers; it requires fundamental change in the world of publishing and authorship.

A 1965 study learned that only 6.7% of children’s books published in the preceding three years had featured any Black characters. Meanwhile, in 2013, another study found that only about 10% of children’s books featured people of colour from any background.