Age of You: MOCA’s latest is merely a showcase for its curators—and not the artists

Age of You, MOCA’s current exhibit, intends to explore what it means to be an individual in the face of accelerating technology and what it means to exist in a society in which our personal data has become the most important commodity under late capitalism. The exhibit is divided into thirteen chapters, collectively curated by Shumon Basar, Douglas Coupland, and Hans Ulrich Obrist.

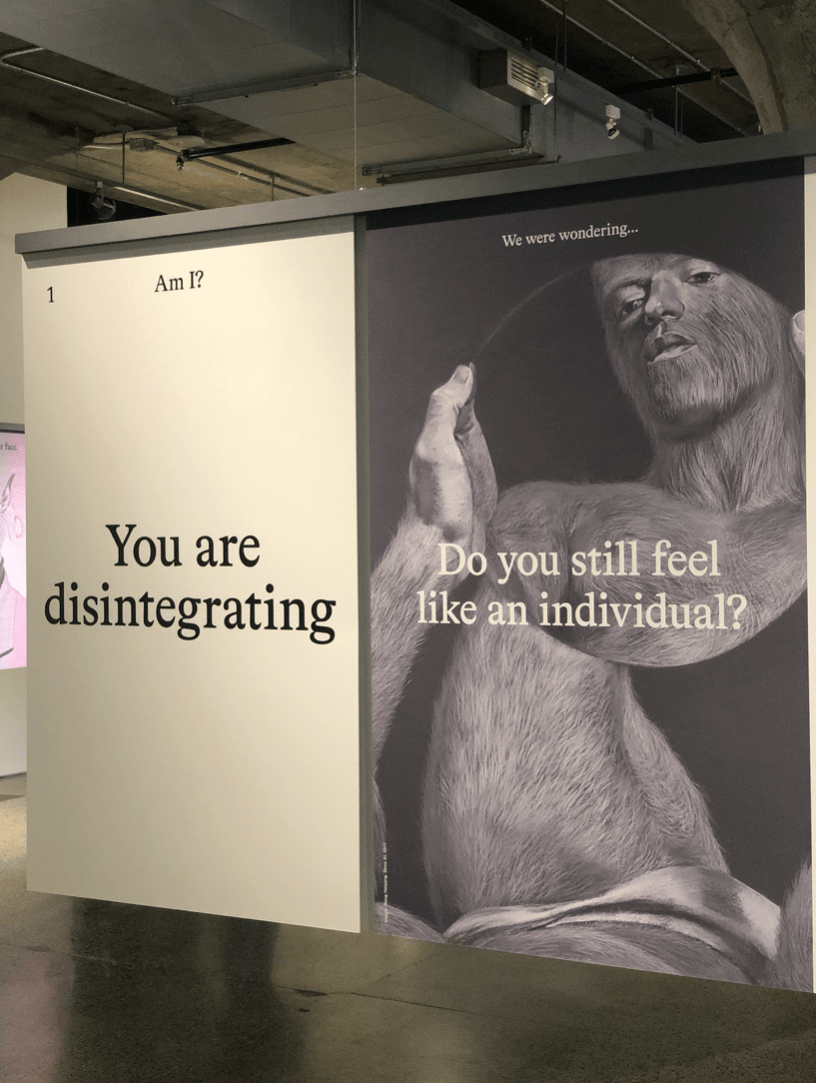

Age of You isn’t so much an exhibit made up of individual pieces on the subject of data extraction as it is a glorified PowerPoint presentation. Most of the chapters are made up of photographs that are overlaid with bold statements, all of which are written by the curators. In the process, the work of these artists—save a few standalone pieces—merely serve as backdrops for the curators to declare their point of view as they promote their thesis about our current relationship with technology. As you explore the exhibit further, you get the sense that the curators are more interested in selling the thesis of their forthcoming book, The Extreme Self (for which Age of You acts as a preview), than they are in showcasing the work of these artists and allowing the work to speak for itself—which is a shame.

Age of You isn’t so much an exhibit made up of individual pieces on the subject of data extraction as it is a glorified PowerPoint presentation.

The centralization of the curators in this exhibit wouldn’t be such a problem if they actually had more interesting things to say. Most of these chapters assault audiences with alarmist statements in bold text, as if to affirm that these statements are the Truth. Statements such as “The Extreme Self has a hard time sitting beneath a tree and contemplating the universe” or “is it hard to be an individual when being part of a crowd has never been easier?” are intended to scare visitors about the contemporary state of our society. The overarching goal of Age of You seems only to berate how millennials engage with current technology and social media. But this goal to provoke isn’t accomplished with much subtlety, and what’s more, leaves little space to open up a more nuanced discussion about our cultural landscape.

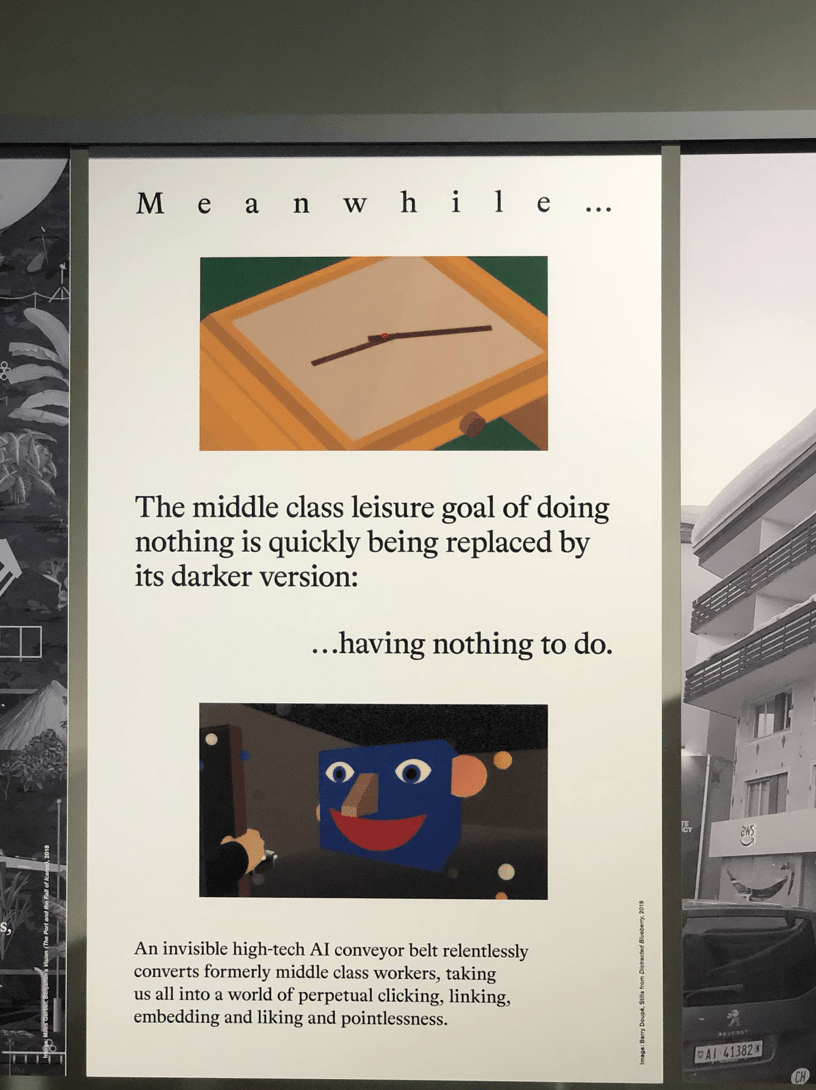

Some statements ring hollow. Chapter 4, Post-Work, for instance, critiques how increased automation will leave people jobless, while Chapter 10, 0.0001%, has a panel that insists that “The middle class leisure goal of doing nothing is quickly being replaced with its darker version:…having nothing to do,” painting a society consumed by its obsession with social media to the point of having nothing else.

A panel from Chapter 10: 0.0001%, imagines a future in which advancements in AI leave people stuck in a repetitive loop with social media.

But these statements ring false in light of reality: although advancements in technology have always been promised as a solution to reducing people’s workload, today, most people are working longer hours per week than they were 30 years ago. Gone is the middle-class promise of a 40-hour work week sustaining a good standard of living in Western cities. Today, in a hyper-competitive gig economy, careers are often made up of multiple jobs with little job security, with people taking on a conflux of contract positions, unpaid internships, and shadow work just to get by living in cities that are increasingly gentrified and unaffordable. Social media often exists as an escape from this reality because we’re too tired at the end of the day to do anything else. This is a current crisis of living under late capitalism—as job opportunities shrink, our productivity only increases while our mental health deteriorates—and so we are often drawn to our phones for ways to distract, and to pleasure ourselves under the condition of having very limited time to create meaningful personal lives.

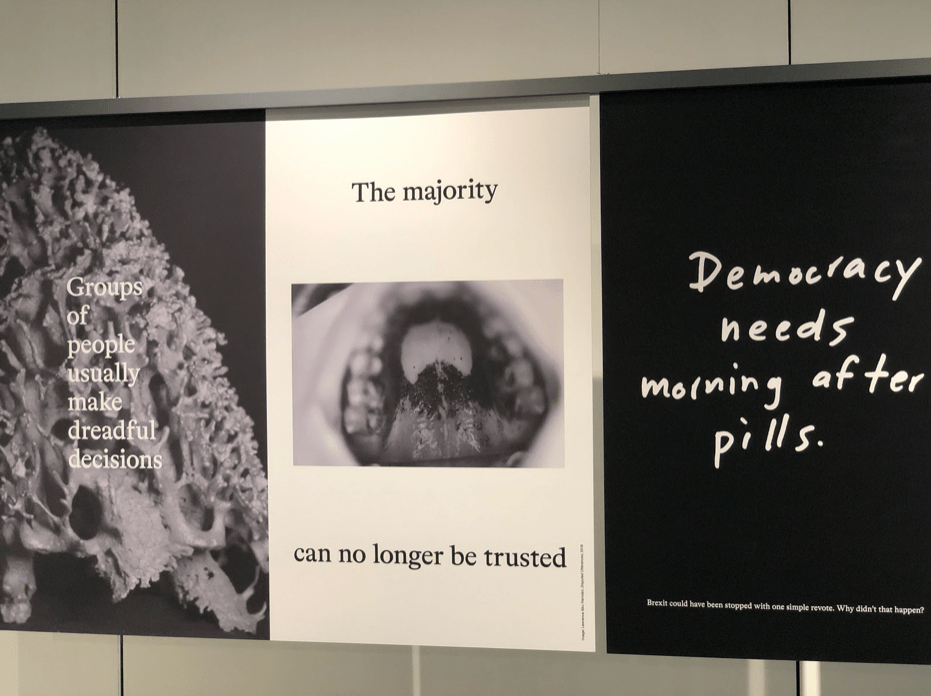

Age of You also fails to engage with a more interesting question: what does it mean to install an exhibit critical of our lack of privacy, our ownership over our data, and our general addiction to social media, when our experiences of museums have radically changed with the practice of publicly documenting our experiences? What does it mean for an exhibit to critique how we use Instagram, or “selfie culture,” and yet be designed in an Instagram-friendly way? While the statements these curators have chosen are meant to provoke, they are also designed to make for an appealing post on Instagram. The statement “Democracy needs morning after pills” scrolled across a black background resembling a chalkboard is precisely the type of pop work marketable for social media consumption.

Chapter 11: The End of Democracy, attempts to consider the function of democracy in a ‘post-truth’ era.

If Basra, Coupland, and Orbist had chosen to focus more seriously on the implications of this state of affairs, Age of You would have made for a more complex engagement with the topic of how we exist as individuals today in the face of ever-expanding technology, rather than a pop exhibit littered with shallow provocations, with little else beneath the surface. The heavy-handedness of the curators ultimately does a disservice to the subject matter and the artists on display.