The “Sad Girl” Reduction

On the epidemic of online, self-proclaimed “sad girls” and escaping the patriarchal performance

In a video for Crack Magazine, Japanese-American singer-songwriter Mitski makes the following statement: “You know, the sad girl thing was reductive and tired like five, ten years ago and it still is today,” in response to a fan tweeting that the day on which Mitski releases new music is a “big day for sad bitches.” Mitski’s statement is one we’ve been hearing a lot lately, in response to the onslaught of internet “sad girls,” who seem to have made it their mission to reduce popular media made by or about (young) women to a canvas that perfectly depicts their sadness. As a consumer and enjoyer of art that often gets the “for sad girls” label slapped on it, hearing Mitski’s response, I couldn’t help but agree with her and empathize with her frustration at having her art reduced to a pseudo-identity, but I also found myself feeling a sense of sympathy and understanding for the self-proclaimed “sad girls.” Often when people critique the young women who assign this label to themselves or certain media, they do so in a manner that comes off as ridiculing the women in question, instead of one that attempts to understand where these young women are coming from or why they cling to this label as strongly as they do. But just as the media in question has a lot of nuance and complexity beyond the reduction it gets subjected to, so too does this phenomenon of online, self-proclaimed “sad girls.”

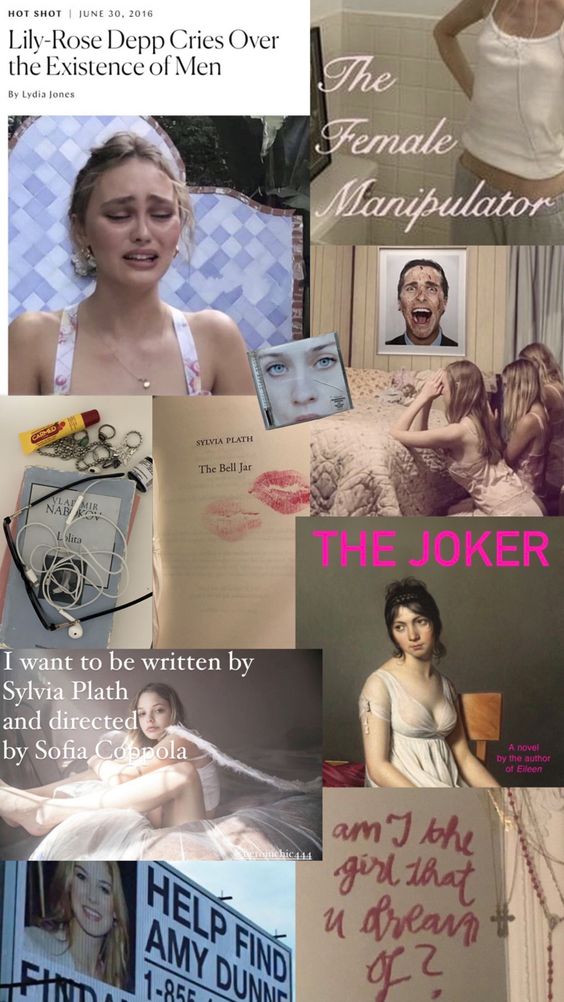

We’ve all seen the posts. The ones with collages which almost always contain a photo of Ottessa Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation and Fiona Apple’s When the Pawn… with a big fat ‘Sad Girl’ label attached to them, or the ones (jokingly) claiming that therapists must hate female artists such as Phoebe Bridgers, Mitski, and Taylor Swift. On TikTok, movies and books are being sold to people as “for those who like the ‘sad girl’ aesthetic”; it’s become impossible to consume media made by female artists without bumping into this phenomenon.

I could try and say that I was never sucked into the (false) comfort provided by this label, but that simply isn’t true. The truth is, it was comforting at first, to see that some of my favorite artists and books were finally getting the appreciation they deserved, to feel like I was not alone in relating to said media’s depiction of the complexity of girlhood. I do truly believe that these posts started out as just that: a celebration of art that is able to capture the nuances of coming of age, mental illness, and trauma, specifically in relation to the female experience. It’s just that somewhere along the way, the nuance of the art in question was lost and the admiration revealed itself to be a reduction. Suddenly, girls on TikTok and elsewhere on the internet were proudly proclaiming that they were in their “Fleabag era”–referencing the titular, self-sabotaging character from the show Fleabag, who sleeps with her best friend’s boyfriend–and saying how the main character of My Year of Rest and Relaxation–the same one who is blatantly racist and uses her mental illness as an excuse to be an asshole–is “so relatable.” It’s safe to say that I became very uncomfortable with and wary of this “movement” at that point.

While it is comforting to find media that validates one’s experiences, once such media turns into a way to promote all around shitty behaviour, one has to take a deeper look into this “sad girl” phenomenon. Unfortunately, but perhaps not shockingly, it can be traced back to the good old patriarchy and the performance it subjects women to. From being told to “sit properly,” encouraged to bite our tongue, and urged to act and dress “more feminine,” young women have always been taught: whatever you do, do it gracefully, do it elegantly, do it beautifully. In Megan Nolan’s novel Acts of Desperation, a novel that is frequently recommended under the “for sad girls” banner. Its main character, a woman navigating a turbulent and toxic relationship with a man, exclaims: “I was wallowing in the glamour of my sadness. I read an article in Vogue around that time which said something like: ‘This season’s looks lean towards Gothic drapery, knee socks and heavy eyeliner, showing something that every teenage girl knows: that sadness can be a kind of beauty.’” It doesn’t matter that growing up, you feel something churning and writhing within you in response to recognizing the seeds of what you’ll come to understand as sexism or misogyny, as the performance must always be maintained. While young women are typically not discouraged from crying, a different rule exists for any feelings or emotions deemed to be “ugly” or “undesirable,” such as anger or rage, both feelings that women are all too familiar with. Over and over, young women are told to suppress their anger, to “calm down,” to not “overreact.” So, why the name “sad girl”? Why not “angry girl”? In keeping with the performance of it all, it seems fitting that an “umbrella” term, such as sadness would come to define this phenomenon, as it is a more palatable way of encompassing the works it aims to (re)present, works which, more often than not, discuss female rage (albeit underlying or disguised as something else). This is not to say that sadness and depression are not also the reason for the word “sad” taking precedence over a word such as “angry,” for example, as those are certainly also pillars of this pseudo-identity.

Understanding this, it makes sense that young women find solace in the works of artists, like Mitski, who shamelessly and honestly discuss topics, such as body image, “toxic” relationships, and the struggles that come with living with mental illness, and it is especially unsurprising that a lot of the music and books, etc. that young women place in this genre often covertly or overtly feature female rage. It’s why hearing Phoebe Bridgers release a guttural scream at the end of “I Know The End” or seeing the titular character of A24’s Pearl freely express herself, loudly crying out (often in the face of men) is so cathartic: they allow us to vicariously live through them, to relish in their “breaking” of the performance, which we may feel we cannot do in our real lives. Being exposed to this art feels almost revolutionary in the momentary liberty and catharsis it provides, and is likely what draws young women into claiming the “sad girl” persona.

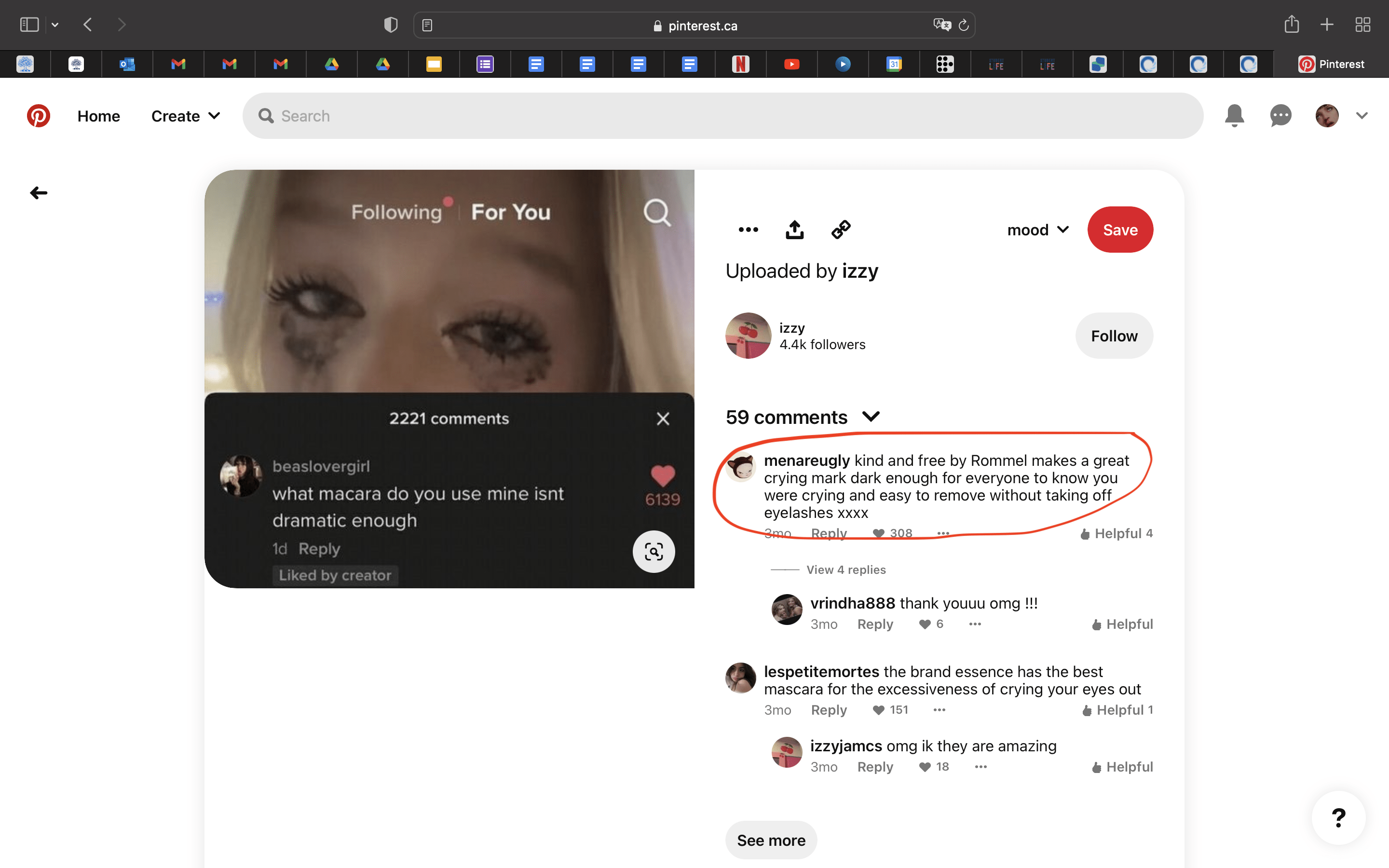

Unfortunately, this isn’t all there is to it. Like other aspects of womanhood, this “sad girl” persona has turned into an “aesthetic” or a performance, if it wasn’t one from the start. I was scrolling through Pinterest, as one does, when I came across this post:

If the post itself hadn’t caught my attention, the comments certainly did. If someone is so deeply upset that they’re crying…why would they want everyone to know that, to see them like that? What other way is this meant to be understood as other than a blatant performance? A performance of the perfect “sad girl,” the one who makes a spectacle or a presentation of her sadness, the one with dripping mascara on her face, still striving for prettiness though she feels unwell. Even if no one is privy to that performance, the need to perform has been so internalized–à la Margaret Atwood’s male fantasy quote–that these “sad girls” could be alone in their rooms with no one watching, and yet they would still apply a fresh coat of mascara before breaking down…

I think that we must also address the elephant in the room, the one that we, in this postmodern, “hyperwoke” society, don’t often want to talk about, which is that for a minority of these “sad girls,” their performance is a feeble yet learned attempt at seeking out male validation. Often, when these girls do not receive the desired male response (or a response at all) to their meticulously-crafted performance, the shock or disappointment at not getting the reaction they were “promised” can push them deeper into this constructed identity. The main character of Acts of Desperation states: “I was shocked that he was not impressed and cowed by my delicacy, as other boys had been. Why did he not find my frail, picturesque sadness alluring?” The only way forward becomes an overindulgence in this “identity,” to mask the rage and anger that comes bubbling to the surface at the realization that we had been taking part in this performance, after all, the one we initially believed this movement to be a chance to break away from. The same character explains: “I thought of all the worry I had solicited in one way or another from Ciaran and from other men, with the food…and the crying and the sex, the whole great presentation of my rage and hurt, anger like a performance, anger at everything they’d done to me or hadn’t bothered doing to me.” It’s worth thinking about how much of this identity, which claims to carve a space for women to embrace and discuss the feelings (often surrounding mental illness) and characteristics denied to them by the patriarchy, is in reality still catering to and further performing for the patriarchy.

What is also bewildering about this ordeal is that, ironically, so-called “sad girl” media rarely promotes the values that “sad girls” ascribe to it and is often not encouraging the consumer to relate to its characters. In fact, a lot of the time, the female characters that “sad girls” claim to relate to, are bound and forced to partake in the same performance that young women in real life feel bound to. For instance, in Fleabag: The Scriptures, the author and creator of the show–which has become one of the pillars of the “sad girl” identity–Phoebe Waller-Bridge explains who Fleabag is and how she came to be, stating: “One day she [Fleabag] woke up with an audience watching her so she did the only thing she could…she put on a show.” Throughout the show, it becomes increasingly obvious that the main character is “performing” for the audience as a way of coping with her self-destructive behavior, but she is in no way praising or encouraging others to relate to or mimic her behavior–yet the term “Fleabag era” has been used so often that it’s not even clear anymore what these girls mean when they use it. Are they depressed? Have they been self-sabotaging? Have they also slept with their best friend’s boyfriend? It’s unclear. And it’s unclear how self-ascribing this term helps these girls beyond soothing their ego and allowing them to applaud and perpetuate shitty, self-destructive behaviour. This is not to say that one can’t find comfort in Fleabag’s character or even relate to her a little, but reducing the whole show to a throwaway term is then not only a reduction, but also a willful misrepresentation. So, no, I don’t think that many of these young women are in their “Fleabag era” because if they truly were, they would have understood the final moments of the show–when Fleabag shakes her head at the camera, silently asking the camera/audience not to follow her around anymore–as Fleabag’s attempt at breaking the performance and potentially seeking change. If they truly were in their “Fleabag era,” these young women would have followed suit in their own lives, instead of continuing the performance that not even their biggest “idol” wants to be a part of.

What I am more concerned about, is that although relying on this one-dimensional identity is a coping mechanism for many of these young women, who are trying to find some way of grappling with their mental illness, I don’t think that this coping mechanism is one that is helpful to them in the long term; in fact, it can be quite harmful. I say this because a lot of the work that becomes popularly associated with the “sad girl” label, particularly in terms of literature and film, echos the statement: “I feel like shit, but I’m still so pretty, and gorgeous, and attractive, and skinny,” whether verbally or aesthetically, and I think that the fixation on these works sends the message that it is only “acceptable” for women to be mentally ill and to talk about their mental illness if they are doing so in an “aesthetic” (often unhealthy) or glamourized way. This then shifts the focus of these internet communities from being about finding comfort in works about young women grappling with mental illness, while seeking help or working on oneself, to aestheticizing one’s pain and suffering, and yet again, prioritizing women’s appearance over their well-being.

So, where do we go from here? If we’re not in our “sad girl era,” then what are we? Hopefully, more understanding of where these “sad girls” are coming from, but also critical of their actions. Hopefully, we are also trying to find some way out of this patriarchal performance, a tangible way out, one that doesn’t exist only within the media we consume. For socioeconomic and safety reasons, a “way out” of the patriarchal performance may not even be possible for many women, but I believe that the performance as it pertains to the “sad girl” phenomenon can be broken, bit by bit. I don’t think that breaking this performance is going to be easy, especially not if you’ve been on the internet long enough. If it was, I don’t think we would feel this attached to “sad girl” media. But I believe that we must try to break it, in whichever way works best for us as individuals, whether through a social media detox, therapy, or something else. Bit by bit, we must try to break away from this performance–before it breaks us.