Vilhelm Hammershøi: The End of Waiting

“I have a pupil who paints most oddly. I do not understand him, but believe he is going to be important and do not try to influence him.”

—P. S. Kroyer, 1885.

Danish painter Vilhelm Hammershøi was known to be shy, quiet, reclusive, and never quite keeping pace with the revolutionary movements of his time. His interiors are so subdued that they stand out on gallery walls when surrounded by paintings of his contemporaries, most of which are blossoming with colour.

His art, however, didn’t always have a place on these walls.

I believe Hammershøi’s famed set of one hundred interiors embodies his perpetual wait for the recognition of his work by the artistic establishments of his time. His unsuccessful pursuit of acceptance, paired with his inability to adapt to the rapidly developing industry of the Modernist era, inspired this collection of works that were contemplative, detached, yet in another sense, almost oppressive.

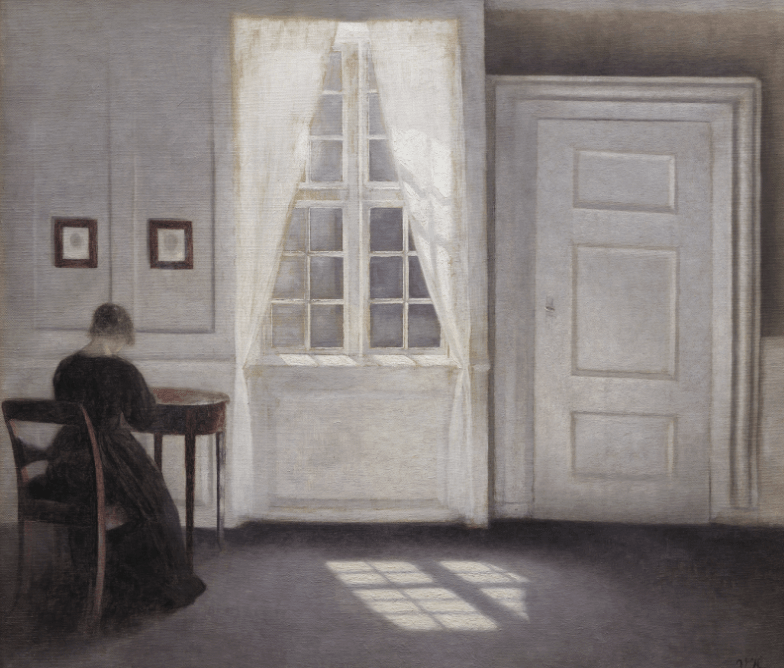

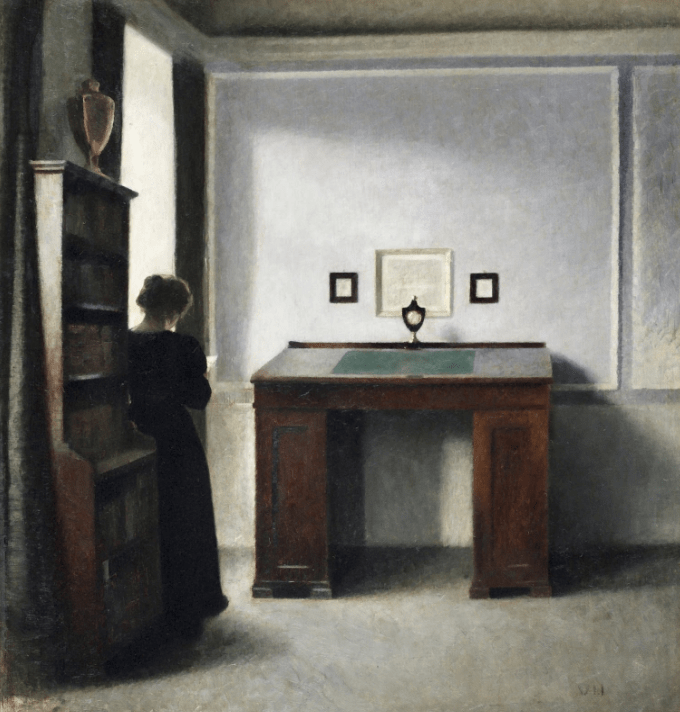

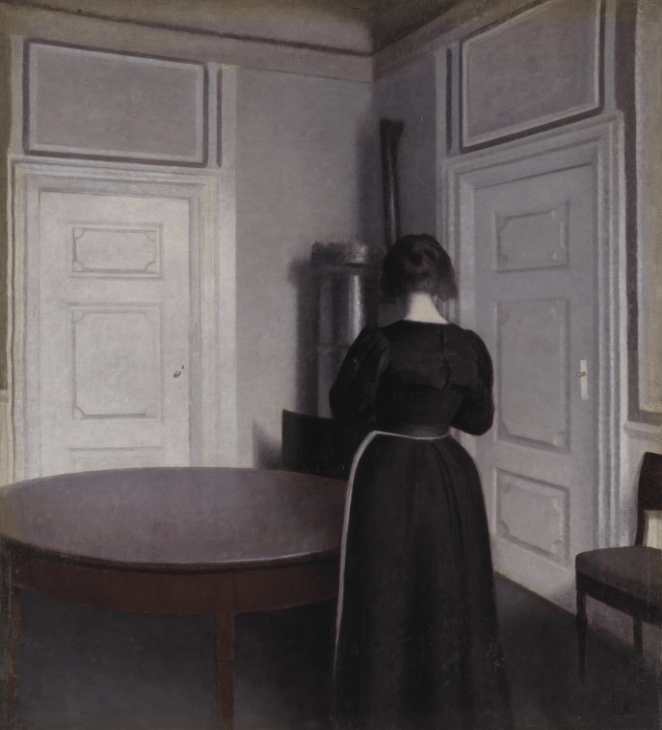

Hammershøi’s interiors all have the same general qualities. He consistently painted with a desaturated palette, so much so that rumours of colourblindness became quite widely circulated. In content, too, he shied away from action. Most of the furniture depicted are pushed back against the walls so that the middle of the room is an empty void. The mysterious black-robed woman turns away, entirely detached from us. Oblivious to her identity and task at hand, we can only feel the static, haunting silence of the room.

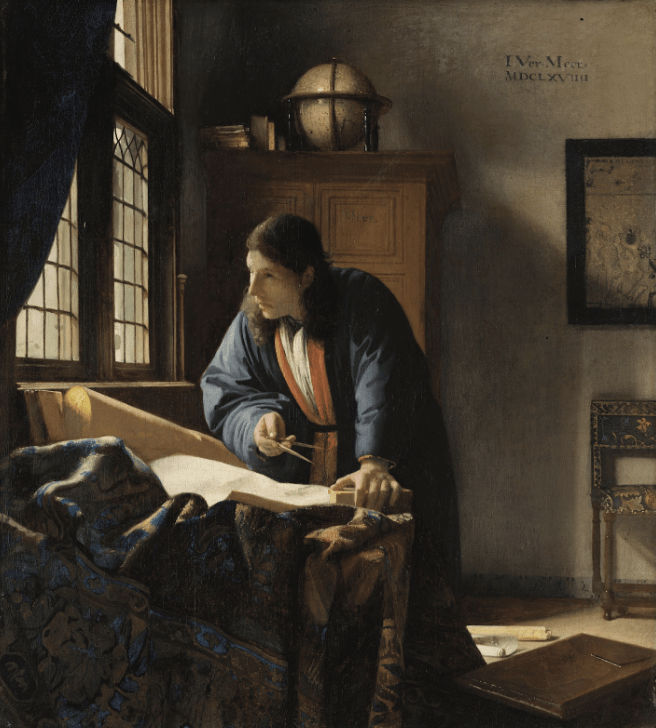

Compare this to Dutch interiors, which often depict a figure performing a task. Even Vermeers, in all their ambiguity, usually offer us a concrete scene to observe, with figures that have an identity: the lace maker works on her craft, the milkmaid performs her daily chores, and the geographer and astronomer engage in their intellectual pursuits.

It was Hammershøi’s personal life that influenced his paintings. Like most artists, painting was one of the greatest joys he found in life. Those who study his works also notice that when he was “working with what he was closest to, he was at his most successful” (Fobert). Artists often live and document their lives through their art. It is no wonder, then, that when a series of misfortunes impeded upon his professional endeavours, his paintings also began to address themes of “psychic alienation, a sense of supreme aloneness in a world suffused with melancholy” (Budick). In his later years, a patron had asked Hammershøi whether he was able to sell his art, to which he reluctantly replied in the negative. His masterpiece, “Five Portraits,” painted from 1901 to 1902, was intended for the Danish National Gallery, but the institution rejected it; his friends report that it was “a blow from which…Hammershøi never recovered” (Yule). Finally, after another renowned portrait, admired by many and expected to win a prize from the Academy, failed to do so, he began to break away from artistic establishments entirely.

Not only did he encounter many hardships in the world of art, Hammershøi also found it difficult to adapt to the city. Industrialisation created a society that moved and operated more swiftly—amidst the fog, buzzing lights, and bustling streets, Hammershøi felt a desperate need “to hold on to some calm…a counter-reaction to time” (Kaaring). His palette, verging on achromatism, could also be a reflection of the grey soot that devoured London in the process of industrialisation, which Hammershøi himself had witnessed in his various stays in the city.

Perhaps these difficult experiences were the reason why he often painted interiors that were dull, empty, and static. I like to imagine the room in his paintings to be a manifestation of Hammershøi’s mind. Though it was his own home, his depiction of it is not in the least lively. It is a suffocating embodiment of the artist’s unprogressive professional life in a time of immense progression and, at the same time, his pining for a sense of tranquillity in the busy, industrialising city. Additionally, the doors and windows never show the outside, and the woman always stands discreetly with her back turned. In this way, Hammershøi instils a sense of impenetrable distance between the viewer and the scene, and, “by excluding the viewer,…creates a feeling of being imprisoned within the serene apartment, whose toned-down atmosphere begins to resemble that of a grave” (Macklin). It was the grave of Hammershøi’s professional life, his hope of seeking recognition, and his wish for quietude—as was his nature.

I then discovered “Interior with Four Etchings”, which with its calm serenity was quite different from the eerie oppression of his other interiors. Although Hammershøi never lived to see his name cited alongside the Danish masters, perhaps this painting was his emotional resolution to his turbulent career, depicting only an atmosphere of tranquil introspection and acceptance.

It is much less empty, featuring a table with three ceramics and a wall decorated with the four etchings that gave the painting its name. Light penetrates the room through a nearby window that although not visible in the painting, is still immediately noticeable. The mahogany table, chairs, and picture frames, although desaturated, give the painting some colour. Overall, this work is not as oppressive, dark, and enigmatic when compared with the others. It does not have the stifling, grave-like atmosphere of a void, and nor is it as static: perhaps this time, the woman is lovingly polishing more ceramics to ornament the table.

“Interior with Four Etchings” depicts an atmosphere of tranquillity, perhaps one for which Hammershøi had hoped. The room itself, with the etchings on the wall and the ceramics on the table, brings to mind the arrangement of an art gallery. The content of the four etchings themselves are unclear and offer a sense of ambiguity. When viewing the painting, I imagined that they could be anything, because anything can be displayed within one’s own home, unlike the selective nature of art institutions and galleries.

Upon closer inspection, I also noticed how the etchings are decentred and not perfectly straight. The ceramics, too, are not spaced evenly. I wonder if this crooked placement of each object suggests some imperfection in display. No aspect of this miniature gallery is perfect nor professionally recognised, but it has its own place.

If Hammershøi established a distance between his paintings and his viewer to create a sense of exclusion in other interiors, then in this one, the distance served to evoke a sense of private enjoyment and contemplation. After each unsuccessful attempt at appealing to art establishment, Hammershøi may have finally reconciled with his artwork as creations that, in his time, only he could enjoy. This is a tranquillity that exists not only around him, but also inside him. The light shining in from the right of the painting dispels any hint of polluting fog. Hammershøi had cleared his mind.

Sources

Budick, Ariella. “Painting Tranquillity: Masterworks by Vilhelm Hammershøi,” Scandinavia House, New York. FT.com, 2016.

Fobert, Jamie. “The Great Indoors.” The Architectural Review (London), vol. 224, no. 1339, 2008, p. 48–.

Kaaring, Liza. “Wilhelm Hammershøi ‘From the British Museum. Winter’ 1906.” Fuglsang Kunstmuseum, Fuglsang Kunstmuseum, https://fuglsangkunstmuseum.dk/en/artikler/vilhelm-hammershoei-fra-british-museum-vinter/.

Macklin, Harri. “How to Paint Nothing? Pictorial Depiction of Levinasian Il y a in Vilhelm Hammershøi’s Interior Paintings.” Journal of Aesthetics and Phenomenology, vol. 5, no. 1, 2018, pp. 15–29, https://doi.org/10.1080/20539320.2018.1460112.

Yule, Eleanor. “Michael Palin and the Mystery of Hammershøi.” BBC4, performance by Michael Palin, 2005.