In Their Small Faces

We’re so excited to present Acta’s (possible first ever!) publishing of creative non-fiction! This simple and beautiful prose piece by Sarah Bigham looks deeply into how homes function, intergenerational family effects and challenges that follow you around many years after they are over.

It was well past 10 p.m. One was shrieking happily while jumping on his bed, wearing only half of the superhero pajamas I attempted to wrangle him into hours ago. Another was running in circles in the playroom, thumb in mouth, the arm of a plastic robot gripped in his small fist. The last one was banging on a toy piano and singing at the top of his lungs.

I was in high school. These were not my kids. And I was exhausted.

*

I spent years of my life caring for other people’s children. I loved them all, albeit some more grudgingly than others. This trio was, quite possibly, my biggest challenge. I had learned to adapt to various households and their accompanying children — carting the chubby red-headed baby with adorable curls on my hip for hours to avoid the tears that fell if he was placed on the floor to play; reading aloud with first graders and talking excitedly about the stories; supervising homework and watching movies with tweens whose parents wanted to go out for date night but weren’t quite ready to have their children stay home alone after dusk.

I had grown up in a home with clear rules about nap time and bed time. Many of the homes where I cared for children had a version of similar rules. Some had a slightly more relaxed timeframe (we put them down somewhere between 7 and 8) while others had an entire timetable taped to the fridge. Over the years, I came to understand that some parents, especially those with children whose very natures craved structure of all kinds, found the timetable reassuring for everyone in the home. With first-time mothers and fathers of newborns, I realized that having a clear and precise agenda is what helped them through the initial sleep-deprived months and gave them confidence as parents.

Some years ago, I unearthed a handwritten schedule with my name at the top. My mother had written it for my uncle when he was helping to care for me, as my grandmother was dying of cancer and her children were taking turns at her bedside. Uncle Bob was the youngest of the three siblings and, as a bachelor in his early 20s, had likely never cared for a baby. The schedule gave him something concrete to follow, a roadmap to success.

During one interview with a new mom in search of occasional childcare, I asked about her baby’s schedule, including nap times, feeding times, and how often her child was bathed. She seemed shocked that I, as a non-parental teenager, would even think to ask such a thing. She later confided that the first child she had ever diapered was on her own. I was stunned. I knew from years of spoon-feeding and rocking to sleep and applying bandages and drying tears and giving bottles and straightening toys and playing Go Fish and cleaning up the various things that flow freely from bodily orifices of the young, that I loved children, deeply, but did not want my own. Somehow this woman wanted a child without ever experiencing any of that. Perhaps it is that kind of guileless optimism that helps keep our species alive.

Spending time in other homes taught me a lot about people in general. Inviting someone into your home, asking that person to care for your children, and leaving that person unattended in your house requires trust and confidence, something I could sense every time I met a new family and watched the parents (especially the moms) walk out the door with just a hint of hesitation, a backwards glance. I knew that I was guarding their most precious people, and I wanted to be worthy of that trust. Babysitting (such a misnomer) allowed me to see how the blend of families functioned, introduced me to keeping a kosher kitchen, showed me the difficulties faced in raising children who could be so very different from their parents, challenged me to be a stable presence in the lives of kids whose circle of adults was spinning out of control, gave me the privilege to be privy to the secrets of four year-olds, and showed me the many ways people spoke to the ones they loved most.

I learned to adjust to each household when I walked in the door and how to interact with the children in ways that made them feel safe and content.

But this trio was nearly impossible.

*

I could always get my charges to sleep. It might have taken a little extra initiative at first, but I knew the importance of a routine and building in books and favorite stuffed animals and songs and time in the tub. I could always get children settled for the night. But not this crew.

I was slightly surprised the first time I sat for this family and was given no instructions at all, other than some vague mention of what foods were available to serve for dinner. What astonished me was that the parents, when they returned home, did not seem at all fazed when I confessed that the boys were still awake. I was so apologetic, and explained that they were in their room, with the lights out, but they were not yet sleeping. I was thoroughly embarrassed, but the parents didn’t flinch. The dad muttered something to the effect of just like usual with a half grin as he headed up the stairs to bed. The mom told me that they didn’t have bedtimes. She let them play until they fell asleep. “Next time,” she said, “just pick them up off the floor once they have fallen asleep and put them in bed.”

I was flabbergasted. This is the plan? I thought. Really?

I was not looking forward to future visits, but caring for children was how I earned money throughout my school years, so if a parent called and my schedule was free, I signed up. I cared for these three boys several more times before deciding that enduring books being thrown wildly at my head in moments of glee, toys being tossed with abandon, and nonstop ruckus continuing until midnight, from little ones who should have been getting so much more sleep than they were, was too much. I declined the next request and never returned.

Even as someone who had grown up in a large family with constant visitors and multiple pets, I was simply overwhelmed by that trio. At the time, I had not heard of free-range approaches to development, nor had I learned about child-centered parenting in college psychology classes. I was used to order and schedules and children who, for the most part, did what adults told them to do. I felt outnumbered, ineffectual, bone-tired, and defeated. What I had thought was my adaptable style of nurture and care was more limited than I realized. It was the first time I considered myself a failure in working with children.

*

Many years later, I heard that the mother was a child during the Vietnam War. Her older brother had been drafted, sent to basic training, shipped overseas, and killed, while she watched the nightly news with her parents, seeing the body count tallies on the screen.

The chaos in that house of boys finally made sense, and the guilt I carried about my perceived failure began to lift as I considered the circumstances of those children and the family history that surrounded them from the moments of their birth.

Their mother had lost a brother, a child himself, in a war he did not start and did not choose. She gave birth to boys, all of whom looked so much like her that they must have been a reminder of her lost sibling as she gazed down at their small faces. How could she set limits on them? How could she say that play time was over? Of course she wanted them to squeeze every moment of pleasure from each day, stopped only by sleep and never by arbitrary rules or timetables. She may have lost her brother in a faraway land during a time of fear, but she would do all she could so that her little coterie of sons would be always, always surrounded by fun, forever alive and ceaselessly in motion.

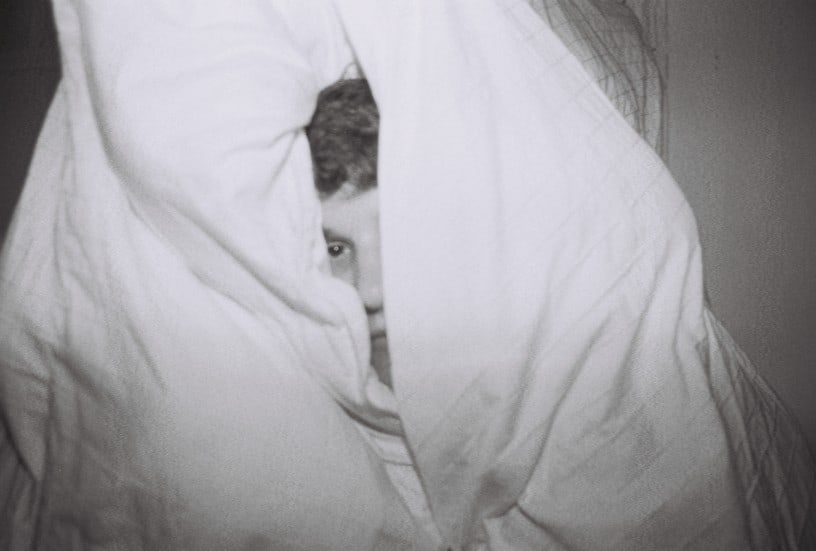

Untitled

Visual by Emma Doerksen

she would do all she could so that her little coterie of sons would be always, always surrounded by fun, forever alive and ceaselessly in motion

Sarah Bigham

writes from the United States where she lives with her kind chemist wife, three independent cats, an unwieldy herb garden, several chronic pain conditions, and near-constant outrage at the general state of the world tempered with love for those doing their best to make a difference. Find her at www.sgbigham.com.

Emma Doerksen

is a cinema studies student and is the editor-in-chief and co-founder of Cinema Six magazine. Emma also enjoys painting, photography, filmmaking, hiking, and queer theory.